Born 254 years ago on December 16, 1770 (baptized, December 17th), Ludwig van Beethoven changed the course of music and cultural history in his just fifty-six years of life (d. 1827).

One of our core missions is to educate our audience about Beethoven’s life, to share his known and lesser-known compositions, and to explore and question his legacy in creative ways.

While he is world famous and some of his “tunes” have been heard around the world, most people only “know” Beethoven on a surface level. His birthday month every year is a perfect opportunity for all to dig a little deeper into lesser known aspects of his life and music.

Lastly, our work is powered by public support. Please consider making a one-time or recurring tax-deductible contribution now:

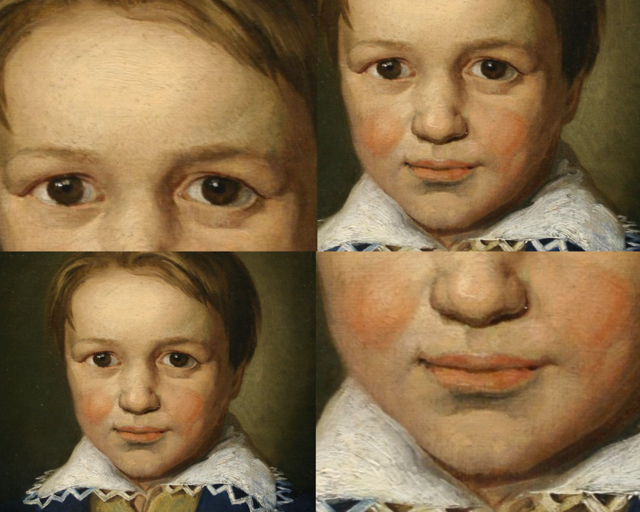

Beethoven’s Portrait as a Thirteen Year Old

Or the Mysterious Appearance of the Child Beethoven in 1952

George Lepauw, December 22, 2022

When you look up Beethoven on the Internet, you usually see, pretty quickly, a portrait of the composer as a child. We take it at face value, and assume that this is verified historical information. In fact, Beethoven’s talent and fame from an early age gives us reason to believe that his first portrait was made when he was indeed still a child. While this may be a fair assessment based on what the Internet tells us at first glance, the real story behind this portrait is much more convoluted than we realize. And until I began to look into it, I myself had no idea how complicated this story would be! More importantly, this portrait’s attribution may be a case of revisionist history.

First, we need to contextualize this story.

Beethoven was a recognized talent from a young age, and his fame as a pianist and composer increased significantly as a young man. This earned him the honor of having many representations made during his lifetime, before photography, invented by Nicéphore Nièpce in 1822 but not frequently used until the 1840s after Beethoven’s death, made it easy to capture someone’s likeness with precision. After his death, a multitude of images, both realistic or vaguely reminiscent of the composer, exploded. And to this day, new images of Beethoven continue to flourish.

In fact, he is probably the composer whose image is the most widely reproduced and disseminated in the world, which has in part helped to turn him into a true pop icon, an achievement crowned when Andy Warhol, the king of pop art, created four screenprints, made just before his death in 1987, based on the authentic portrait from life of the composer by Josef Stieler in 1819.

Most representations of Beethoven fit the general perception people have of the artist as an inspired rebel, a sort of early rockstar, willing to cast away the traditions of wig-and-livery suited artists employed in the households of the nobility or as members of the Church.

Beethoven started out his professional life very young in such a traditional court environment, but quickly broke off from this ready-made career and chose instead a path of complete social and artistic freedom. While he endured some difficult circumstances stemming from his choice to be free, his struggle matched this promethean moment in history when the people of many nations chose to rise up for liberty, equality and fraternity, exemplified most of all by the cataclysm of the French Revolution.

Beethoven’s character, personal style, music and life story perfectly fit the new world order that was arising out of the political, social and industrial changes taking place across the Western world. Beethoven was the perfect symbol of the dawning romantic age, a paragon of the inspired and unique, but tortured, artist. In his case, “fate” had condemned him to become a deaf musician, sealing his legend forever as a modern day Prometheus, a bringer of Light and Beauty to humanity who paid with a form of physical torture for his gifts to the world (note: the myth of Prometheus was particularly in vogue during this period, and Beethoven fit this story line perfectly. Review it here).

While still alive, Beethoven had already, unwittingly, achieved cult status, partly as a result of his deafness and extraordinary ability to keep composing, but also and mostly stemming from his revolutionary way of playing the piano and of composing powerfully emotional music, far from the conventions of pleasant music typically heard in the aristocratic salons of his day. Beethoven excited the fervor of thrill-seeking audiences, and was to music in his day what amplification became to acoustic music in the 1950s.

While this level of fame encouraged artists, publishers, journalists, friends and fans to seek representations of the composer’s likeness, only a select few of Beethoven’s images are deemed to have had a true resemblance to him. More importantly, only a handful were made from life and are thus truly authentic.

On the subject of Beethoven iconography, countless articles and books have been written, two of the best being by scholars Benedetta Saglietti and Alessandra Comini. Every representation of Beethoven, especially those made during his lifetime, has been analyzed, its provenance researched. It would seem difficult today to add anything new to volumes of knowledge on the subject matter. Beethoven is indeed one of the most well-researched and well-documented persons in all of history, and several museums and archives exist to protect and collect the large amount of valuable primary and secondary source materials that have been assembled over the past centuries.

Most people who had the chance to encounter him in life took note of it, whether distant fans or intimate friends. Everyone knew, in his own time, that he was a history-making musician, a heroic figure whose talent surpassed all others, with the exception of the accepted pantheon of composers, Bach, Handel, Haydn and Mozart among them. As his body lay still lukewarm on his deathbed, friends and passersby who had the guts to enter his apartment in the days before he was buried, cut locks from his hair as personal mementos, leaving a hairless head by the time his corpse was put into its coffin.

However awful this sounds, it also shows how famous he had gotten by the time he died. Just consider how large his funeral procession was: twenty-thousand people followed him to his final resting place! And when his belongings were put to auction a few months later, hundreds of collectors came away with bits and pieces of various importance, from furniture and objects to manuscripts and letters, inadvertently spreading Beethoven memorabilia to the four corners of Europe and beyond, an ill-considered historical mistake that has since forced sleuths to search the darkest cellars and dustiest libraries to try to put the pieces of the puzzle back together.

Yet, despite impressive successes in Beethoven research since 1827, there are still parts of the composer’s story which remain unanswered. New elements occasionally rise out of the darkness and into the light, provoking untold excitement. Every few years, some unknown piece or scrap of music, letters, images, objects emerge from private collections, attics, shoeboxes, dispersed in one way or another across the continent and beyond.

Historical events that have ravaged the world Beethoven knew have certainly not helped. In his own lifetime, France even incorporated his birth city of Bonn from 1794 until 1815, technically giving Beethoven French citizenship, but adding a layer of complexity to his family and city history.

The World Wars didn’t help either, and the Soviet occupation of the areas Beethoven spent most of his adult years in, from Vienna to Eastern Germany, Bohemia and Hungary, didn’t facilitate the tracking down of lost materials until the end of the 20th century. Between destruction, pillaging and massive human movements, the disappearance of precious clues to Beethoven’s life was inevitable. And it is not over: who knows what else will be forever lost with the climate and geopolitical catastrophes that our present century seems to be reserving for us?

Yet, surprises abound, as the story of the portrait of Beethoven as a thirteen year old can attest.

Officially discovered in 1952 when it was bought by Dr. Hartwig Schmidt from an auction house in Braunschweig, in Lower Saxony, Germany, we know next to nothing about its previous provenance, other than that it was owned by a Dr. W. Klamann-Parlo who lived in Steinbach/Wörthsee but was originally from Silesia.

The oil portrait was unfortunately unsigned, made on canvas about the size of a regular sheet of print paper (17 x 22 cm). According to an inscription on the back of the canvas (“L.v. Beethoven i. Xiii. Jahr”), Beethoven is identified as the subject of the portrait, at thirteen years old. If this portrait is authentic and as advertised, it would certainly be the earliest known representation of Beethoven, a fact of great historical significance.

A second inscription, on the lower cross piece of the structural frame in the back of the painting, adds that this work was owned by Beethoven’s close friend, the Baron von Zmeskall (1759-1833) (“Besitz Baron v. Smeskall.” [sic]).

Analysis revealed that the portrait was retouched around the mouth and chin within just a few years after it was first made, somewhat changing the appearance of the original based on what ultraviolet scans of the portrait revealed.

The inscriptions referring to Beethoven and Zmeskall are the only formal clues we have that associate this boy’s image with Beethoven. There are no known letters or other documents that make any reference to this work during the life of Beethoven, nothing that would have otherwise given hope that this portrait would one day be found, although we do know of the existence of a diary of Zmeskall’s which has disappeared and could perhaps reveal, if found, some information.

This portrait’s appearance in the 1950s therefore came as a complete and unannounced surprise, further complicating the process of authentication. And there are absolutely no other images of Beethoven from that time in the composer’s life to compare it to, other than a silhouette by Joseph Neesen (1770-1829?) from the time he was fifteen, looking all grown up, which does not help much, although perhaps the most modern technologies could help to analyze all the data and verified images anew.

The portrait was presented to the scholars of the Beethoven Archiv in Bonn in 1968 upon the approach of the bicentenary of Beethoven’s birth in 1970, but they dismissed it without much study as a forgery or as a misattribution. Rightly so?

When its owner, unconvinced by the Beethoven Archiv‘s dismissive assessment, brought the work to Dr. Franz Glück, an expert in Beethoven iconographic studies, and former director of the Vienna City History Museum (Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien, which acquired the painting in 1997) and scientific analysts, the work was at least verified as an authentic late 18th century, at latest early 19th century oil portrait. The handwritten inscriptions on the back of the painting were also deemed authentic, although likely added a few years after the portrait was first completed, perhaps at the same time as the mouth and chin were touched up.

This was the start of a schism within the Beethoven iconographic world, as to this day the issue has not been resolved. There is so far not enough proof to claim that it is, or is not, Beethoven, which leaves us with an unresolved mystery, with partisans of both options.

To better frame the conundrum and help us get a grasp of the potential solutions to this frustrating question mark, let us dig deeper into what we know and what we can infer from this portrait and the context of Beethoven’s life around the age of thirteen.

Answers to some key questions would certainly help! Who made this painting? Was it a professionally made work or an amateur’s? What is the artistic value of this painting?

If done by a professional, someone would have likely commissioned and paid for it, of which no trace has been found in any existing and known record. If made by an amateur or a family friend, whatever the motivation, it could have been done for free or for a nominal fee, requiring no records or receipt of delivery.

Whether the boy in the picture is actually thirteen is not proven by anything within the painting itself, and some experts believe that the child looks younger. This remains conjecture, especially as it is likely the inscription was added a handful of years after the completion of the painting and was not necessarily verified by either the original painter or the sitter, as far as we know.

Frustratingly, there is no indication that this boy has anything to do with music, as there are none of the usual attributes typical in portraits of musicians. Indeed, there is no instrument in the background, no music, no book, no musical symbol of any type, no mythological figure representing the muses or perhaps a Saint Cecilia, the patron saint of musicians. In fact, if this were indeed Beethoven, it could have made sense to include some discreet reference to his famous namesake, his grandfather, a musician who made a great career in Bonn.

But having musical attributes is not a requirement in portraying musicians! Even some verified adult portraits of Beethoven show no symbols of music. Therefore this is neither proof of fraud or authenticity.

Also, the boy pictured has light brown hair, whereas adult images of Beethoven show him with very dark hair; and while hair can indeed get darker with age, this does not help make the case that this is the young Beethoven.

According to the Fischer manuscript, an invaluable document written by the son of the Beethoven family’s master baker, neighbor and landlord and whose family was in daily contact with the Beethovens for several years, Ludwig as a child is described as “short of stature, [with] broad shoulders, short neck, large head, round nose, dark brown complexion; he always bent forward slightly when he walked. In the house he was called der Spagnol (the Spaniard).”

The “dark brown complexion” that earned the young Beethoven this derogatory nickname is clearly absent from the portrait. Then again, this was not considered to be a positive attribute in the late 18th century, and it is possible that Beethoven’s skin and hair would have been purposely lightened by the artist.

The boy’s eyes are, however, very dark and intense, which we would expect of Beethoven based on later portraits and descriptions by trusted acquaintances. His face is somewhat pudgy, still very childlike, with a broad forehead, a somewhat flat nose, full lips and protruding chin, all features which could be linked to the adult Beethoven.

But if this is indeed a portrait of the young Beethoven, it would most likely be a testament to his talent, or perhaps to the intensity of his personality. Why else would a painter represent this young boy if he were not worthy in some way?

Other than the offspring of the aristocracy and the upper bourgeoisie, children would not have usually been portrayed, especially in expensive oil paint, unless there were special reasons to do so.

Beethoven was, however, part of a distinguished musical family in Bonn, his birth city, adding value to his own personal talent.

His grandfather Ludwig (Lodewijk) van Beethoven (1712-1773), a Flemish bass singer born in present-day Belgium and after whom he was named, had been a most-esteemed Hofkapellmeister (Music Director of the Court) of the Electorate of Cologne, the state within the Holy Roman Empire that encompassed Bonn, where the ruler’s seat and court were located (despite the reference to Cologne!).

His son, Johann van Beethoven (1740-1792), was also in the service of the Electorate as a Court Tenor. Although his ambition was to succeed his father as Hofkapellmeister, this never happened due to Johann’s generally poor reputation and management capabilities. In fact, he was rather infamous for his heavy drinking and rowdiness in the local taverns, even if he also had pleasant and jovial sides to his personality.

Perhaps surprisingly, and while Mozart (1756-1791) was not yet an adult, the child prodigy craze he inadvertently inspired was already making many children miserable, Beethoven included. Indeed, even then (only fourteen years separate the two musicians) Mozart’s legendary early life had inspired many parents to emulate the wunderkind’s own story, by pushing their children to be like the young Amadeus and perform all around Europe, making a name and bringing in riches and honors for their families.

This is precisely the ambition Johann van Beethoven had for his own son, at least at the beginning. As soon as the young Beethoven was old enough to play keyboard and violin, which was around his third birthday, his father pushed him relentlessly to exceed expectations, often making him work through the night, or waking him up upon his return from the tavern, sometimes with musician friends who would participate in the nighttime lessons. While the young Beethoven made the most from these nocturnal sessions and progressed rapidly, the neighbors often heard the young boy’s music mixed with frequent crying.

Johann van Beethoven was indeed eager to get his son to perform publicly and start making a name for himself, and for this reason organized Ludwig’s first public performance in Cologne, not far from Bonn, on March 26, 1778, when Beethoven was in his eighth year (Johann claimed that he was barely six, which led to Ludwig himself believing it was true during the course of his entire life, convinced by his father’s lie that he was actually born in 1772, despite all official documents indicating 1770).

On a side note, it is a noteworthy coincidence that the date of Beethoven’s debut, March 26, is also the day that Beethoven died in Vienna, exactly 49 years later, in 1827.

Unfortunately for Mr. van Beethoven, and as far as we know, nothing of note came from this performance, and it is most likely that the young Beethoven did not overwhelm his audience with his talent that day, in flashy Mozartian fashion. This comparison, however, was always unfair to Beethoven, then as now. Beethoven’s talent was just as extraordinary, but expressed through a very different personality type.

Let us not forget that Mozart himself did not conquer the world with a single performance! Had Johann really wanted to build his son Ludwig’s reputation as a young prodigy and done it intelligently, he would have organized many more concerts after this first one, which does not seem to have happened. Perhaps, in this way, the perceived failure of young Beethoven to become an immediate sensation was not so much an issue of talent (often thought-of as inferior to Mozart’s at the same age based on this single anecdote) than of a misplaced career strategy by Beethoven père, or of his inability to be a disciplined impresario.

When we consider that Beethoven was later celebrated for his unique abilities as a performer and showman who could make his audiences cry with the power of his emotional playing, it is hard to believe that he had none of this gift as a child. Clearly, Beethoven had it in him to be a spectacular performer, and needed perhaps just a bit more support at that time to rise to Mozart’s level. But it was not to be, and this was probably for the best (Mozart suffered immensely from his chaotic touring childhood). However, had Beethoven’s fame risen in near or equal measure to Mozart’s at a very young age, the likelihood of having authenticated portraits of Beethoven as a child would have risen proportionally.

While Beethoven may have had a similarly extraordinary musical gift as Mozart’s, their fathers were not nearly equal to each other. Mozart’s father Leopold, who was an esteemed musician and pedagogue in his own right, was smarter and a much better manager to his son and to his daughter Maria-Anna (known as Nannerl, also a brilliant young musician) than Johann van Beethoven ever was. And while he comes off quite hard in the film Amadeus (see the convincing Ray Dotrice as Leopold Mozart in the timeless Milos Forman film), Leopold was undoubtedly a good educator and impresario for his son.

In any case, by the age of thirteen, Ludwig was much more serious and disciplined than his own father, earning himself professional employment as a salaried assistant organist to his teacher Christian Gottlob Neefe (1748-1798), the official Court Organist. In addition, Beethoven was equally active as an all-around freelance keyboardist (organ, harpsichord, pianoforte) as well as violist. He was also working as a continuo player (keyboard accompaniment) and as a violist in the Bonn theater orchestra, where he participated as a pit musician performing the most popular operas of the day, including many by Mozart. While we always imagine Beethoven performing and composing at the piano, it is nice to remember his many instrumental skills, including being an orchestra musician.

The young Beethoven was concurrently making a mark as a promising composer, something he himself clearly wanted to do, as neither his esteemed grandfather nor his father had made any serious attempts in this art form before him. As was increasingly apparent, one of Beethoven’s great strengths and passions was improvising at the keyboard. This skill remained with him until the very end of his life, even if his increasing deafness from his thirties onward made it harder for him to do so. This talent and special interest was the spark of inner creativity that the great composer developed into a fully realized and structured source of inspiration for his future masterpieces.

As early as 1782, at just eleven years old, his first work was published: a set of variations on a March by Ernst Christoph Dressler. On this occasion, his proud teacher, Neefe, published the first press mention of Beethoven’s name in Cramer’s Musical Journal:

“He plays the piano very skillfully and with power, reads at sight very well … the chief piece he plays is The Well-Tempered Clavier of Sebastian Bach, which Herr Neefe put into his hands.”

The following year, Beethoven composed and published his first three piano sonatas, an impressive achievement at such a young age. As they were dedicated to the then Archbishop-Elector of Cologne, Maximilian Friedrich, who was also his grandfather’s former employer and knew the Beethoven family well, we could postulate that it was perhaps he who had this portrait commissioned of the young Beethoven.

But during the year that Beethoven was thirteen, a consequential event happened: the Archbishop-Elector Maximilian Friedrich died (April 1784), and was replaced by the Archduke Maximilian Franz, youngest brother to the reigning emperor in Vienna, Josef II. Luckily for Beethoven, Max Franz was an unusually passionate lover of music. Since the new Elector was even more supportive of the talented musicians in his service than his predecessor, perhaps it was he instead who requested this portrait of one of the most promising musicians in his service. What we know for sure is that the Elector Max-Franz was convinced enough by Beethoven’s talent to finance the young musicians’ first and second trips to Vienna a few years later, investing, as it were, in his future success.

How good are these first sonatas, and would they have been enough to prompt the commission of a portrait? Not many great pianists have recorded them, and they are not counted, and rarely published within the famous compendium of his 32 Piano Sonatas. Nonetheless, they have their value, and some notable recordings, including the following one by the great Soviet pianist Emil Gilels (1916-1985), have been made. In the following extract, he plays the first movement of Beethoven’s E Flat Major Kurfürsten (“Elector”) Sonata (click image or link to play. If nothing appears, scroll down):

This is far from the great Beethoven we know. But it is certainly well-enough crafted music for the court atmosphere of provincial Bonn, on the outskirts of the Holy Roman Empire, and perfectly in keeping with the galant style of the time. The Mozart and Haydn influences are also evidently very present. One can also gain a sense of Beethoven’s technical abilities as a pianist, since he himself would have played these works, which include many virtuosic passages in typical classical fashion.

What can be said with certainty is that, helped or hampered by his father’s disorganized pushiness, envy and ambition, the young Ludwig van Beethoven nevertheless progressed extremely quickly in multi-instrumental performance, improvisation and composition from a very young age, and proved himself serious and disciplined enough to take on paid work in the best musical establishment of his birth region, getting recognized by his state’s leaders for his musical efforts and talents. The young Beethoven legitimately made himself stand out.

By the age of thirteen, Beethoven’s musical reputation in Bonn was firmly established and rising, lending the portrait project a certain legitimacy. If one of the Electors themselves were not the commissioners, another aristocratic patron who perhaps had reason to support Beethoven’s progress might have taken on the commission.

Even if we cannot be sure who commissioned the work, we can probably try to find out who painted it, or at least come up with a shortlist! Here is what we know.

The portrait of Beethoven’s grandfather, now in the collections of the Wien Museum, was made by Leopold Amelius Radoux (1704-1773?), primarily remembered as a sculptor at the court of the Elector of Cologne, although not that much is known about this artist. This painting of the elder Ludwig van Beethoven hung in the Beethoven family house throughout young Ludwig’s childhood, and after he inherited it, he always made sure to hang it in a place of honor in each one of his residences in Vienna.

It would be nice if we could include Radoux on the shortlist of painters who might have made the portrait of the young Beethoven, but it does not seem, at first glance, that the artistic styles match. And more importantly, although we do not have definite proof of this, it seems Radoux died in or around the year 1773, ten years before Beethoven’s thirteenth birthday.

Furthermore, one notices in the grandfather’s portrait the attribute of the musician that he was: a score in his hands, indicating without a doubt what his profession was, which is missing from the young Beethoven’s portrait, and which Radoux would have known to insert in the young Beethoven portrait as well, knowing his family and his own talent.

Perhaps a former student of Radoux’s, then, would have been charged with making the other Beethoven portrait? We cannot dismiss it, but we lack enough information to make such a claim.

A higher probability stems from the portraits made of Beethoven’s parents, Johann and Maria Magdalena van Beethoven. Unfortunately, only engraved reproductions remain from what were also oil paintings, which have not been seen by any known scholar and which could be lost or destroyed. Trying to understand what happened to the originals would be of particular interest in our current investigation, but it would not be easy to do so.

We do have strong reasons to believe, however, that the artist was Johann Benedikt Beckenkamp (1747-1828), who was from the same town near Koblenz, and the same age, as Maria Magdalena van Beethoven, making it likely that he was a longtime acquaintance of hers. He then lived in Bonn between 1784-85 before settling in Cologne, where he had a distinguished career, partly associated with the rising Biedermeier style.

New to Bonn, he was perhaps happy to reconnect with the Beethoven family at this time, which concurs with the depiction of the Beethovens in middle age. Could he have made these portraits as a friendly gesture? Or perhaps in exchange for some services, such as introductions at court? At that time, Ludwig van Beethoven was thirteen, perhaps fourteen years old. Is there any chance that Beckenkamp also painted the young teenager? Or that an assistant or student of his was tasked with this mission? It does not seem so far-fetched to think so, and could be a stronger theory amongst our postulates. But we would have to further study Beckenkamp’s work to make a better aesthetic comparison.

Although less likely, the artist Joseph Neesen (1770-1829?), who made the silhouette of Beethoven when he was fifteen, may have made the portrait of the boy Beethoven a couple of years before, unbeknownst to us. There again, not enough information about the artist exists, although it is most likely that this would not have happened, as it seems Beethoven met Neesen at the residence of the von Breuning family with whom he was close during those years, teaching the family’s children.

Silhouettes were fashionable in those days, and Joseph Neesen was asked to make silhouettes of the whole family one evening when Beethoven happened to be present as well. This seems to be the only reason that this representation of the young composer was made, and not on the independent merit of his talent. It remains, however, the earliest confirmed attribution of a likeness of Beethoven.

But Neesen was the same age as Beethoven, perhaps just a few months older. Unless his precocious artistic talent would have allowed him to make the oil portrait of Beethoven at thirteen himself, it seems highly unlikely that this would be the answer to our mystery. But we cannot entirely brush off even this supposition, as history abounds with surprises!

Yet another, perhaps more promising theory, is that this portrait of the young Beethoven was made in the Netherlands on the occasion of Beethoven’s visit to Rotterdam and The Hague to see relatives of his mothers’ in late 1783, when he was just turning thirteen. On this occasion, he earned important accolades from several performances in prestigious homes and earned surprisingly good money and lovely gifts. Had he decided to continue touring, the young Beethoven would have quickly made a name for himself. Yet, he was certainly too young to continue traveling on his own, and his mother was of fragile constitution (she died of tuberculosis just four years later) and could not have chaperoned her young son.

Nevertheless, Beethoven made a true mark on his audiences, and it is not far fetched to entertain the possibility that a Dutch patron would have wanted a portrait made of the young virtuoso, in anticipation of the great career Beethoven already seemed destined for!

This idea draws a parallel with the young Mozart, who, on a visit to Verona in Italy exactly fourteen years earlier when he himself was also thirteen, had such an experience. While the first portrait of Mozart was made when he was just seven, due to the fame he had already achieved by then, his second portrait from life was commissioned by his admiring Veronese host, Pietro Lugiati, Receiver-General for the Venetian Republic who wanted to memorialize Mozart’s remarkable visit in his city and home.

In the Mozart portrait (sold at auction in 2019 for well over four million dollars), one sees the famous and elegant teenager in his very best attire, with a beautifully powdered wig, rich red coat and even a luxurious ring on his dainty finger. Mozart is seated at the keyboard, with his head turned toward the portraitist. A piece of music is on the stand, and even a violin can be seen in the background if you look carefully (Mozart did indeed play keyboard as well as the violin and the viola). There can be no doubt that the person portrayed is a musician!

We know with absolute certainty, through several letters from Leopold Mozart and Signor Lugiati about the circumstances that led to this painting, and even of the two sittings it took for the painter (attributed to Giambettino Cignaroli) to capture Mozart from life. By a fun coincidence, this portrait of Mozart was made in January 1770, the year of Beethoven’s birth.

We can see then how this would have been similarly possible in the case of Beethoven, whether his portrait as a thirteen year old was made in the Netherlands or in the Bonn region where Beethoven grew up.

All in all, it is clear Beethoven’s early years were not as dazzling and adventurous as Mozart’s, though Beethoven did get plenty of accolades on his local scale. Whether Beethoven’s portrait is authentic or not, we do know that he was never as well dressed and coiffed as Mozart! “When Ludwig van Beethoven was a little older, he was often dirty and negligent” recalled Cäcilia Fischer. It is likely, however, that Beethoven did clean up and dress properly when at sixteen, in 1787, he had the chance to meet Mozart in person and to play for him, on his short, first visit to Vienna.

In regards to the “Beethoven as a thirteen year old” portrait, the mystery remains unsolved, but I believe we have at least helped to give a frame to our ongoing investigation. There is still some hope that further clues could be revealed, which would help us make a better assessment of the case in coming years.

Have all leads been explored in the Netherlands? Or even in Bonn and Vienna?

If there were a way to trace the portrait’s provenance before its re-emergence in 1952 by doing further research on Dr. W. Klamann-Parlo, who owned this portrait prior to its sale in 1952, we could learn where this painting was during and before World War II. How, where and when did he get it?

We could also dig deeper into the life and papers of the Baron von Zmeskall, who may have jotted something about this in his lost diary.

And perhaps we should also study the way the boy in this painting is dressed, to see if, from a fashion standpoint, it would have been possible for Beethoven to have worn this style of clothes in the early 1780s in Bonn (unless he was wearing clothes given to him while on his trip to the Netherlands).

Have we missed anything else in our analysis? Please give us your take! And if you have any further leads, or thoughts, we definitely hope to hear from you.

I will continue to explore Beethoven’s life through his portraits in future articles, as a way to learn more about him and his times.

Send your thoughts to: ibp [at] internationalbeethovenproject [dot] com

Main Sources:

- Geiser, Samuel: About the portrait of Beethoven as a 13 year old, translated and annotated by Rita Steblin, 1989 (https://www.beethoven.ru/node/568)

- Saglietti, Benedetta: Beethoven, ritratti e immagini: Uno studio sull’iconografia, Torino, De Sono Associazione per la Musica, 2010

- Comini, Alessandra: The Changing Image of Beethoven: A Study in Mythmaking, New York, Rizzoli, 1987, new edition 2008, Santa Fe, Sunstone Press